On this page:

New to practice notes?

Planning practice notes give technical advice about the planning system, each dealing with separate aspects of the system.

This practice note may be read alongside Planning Practice Note 98: Permit Applications in Waterway Corridors.

What is a waterway?

Waterways are defined in various legislation and policy frameworks. The Water Act 1989 defines a waterway as a river, creek, stream, watercourse or natural channel and may include features like a lake, lagoon, swamp and marsh. Other definitions include:

- Aboriginal Heritage Regulations 2018: includes artificially manipulated waterways and land regularly or intermittently covered by water.

- State Planning Policy: refers to waterway systems including rivers and riparian corridors, lakes, wetlands and billabongs.

A waterway does not include:

- artificial channel or works which diverts water away from a waterway, such as an irrigation channel.

- water collected in private dams or natural depressions not forming part of a defined waterway.

Why waterways matter

Waterways are central to the health of our environment, communities and economy. They provide:

- clean drinking water and other uses

- places for recreation, culture and connection

- critical habitat and biodiversity

- cooling green spaces in our cities and towns.

Waterways also hold significant cultural, spiritual and customary value for Traditional Owners.

Victoria’s growing population and a changing climate are placing increased pressure on our waterways. Impacts such as more intense rainfall, reduced flows and increased urban runoff can degrade waterway health and increase flood risks.

Communities expect rivers and lakes to be healthy and accessible. Healthy waterways also support liveability, resilience and economic productivity.

The role of planning

Strategic planning can help protect and enhance waterway systems at a state, catchment, corridor, reach scale or site to:

- coordinate land and water management

- direct development away from sensitive or high-risk areas

- build resilience to climate change and population growth

- embed Traditional Owner knowledge and aspirations

- deliver benefits for nature, liveability and community wellbeing.

Planning can provide long-term direction for managing waterways as integrated natural and cultural systems. It also enables more effective collaboration across public land managers, local government, Traditional Owners and the community.

Principles for waterways planning

Recognising waterways as living entities

Recognising waterways as living entities acknowledges that rivers, creeks, wetlands, other waterways and their surrounding lands are alive and interconnected. It affirms their inherent right to exist, thrive and evolve.

This understanding has long been held by First Peoples, who maintain deep, reciprocal relationships with waterways and view them holistically. It recognises that their environmental, cultural and social dimensions are integrated and inseparable. It brings together traditional ecological knowledge and contemporary science, recognising that the health of waterways is inseparable from the wellbeing of Country and community.

For Birrarung (the Yarra River), the principle of living entity is enshrined in legislation and supported through the planning system. Responsible public entities (RPE) are required to care for the river and its lands in accordance with the Yarra River Protection (Wilip-gin Birrarung murron) Act 2017. Similarly, the Waterways of the West and Rivers of the Barwon (Barre Warre Yulluk) are also recognised in planning schemes as living entities.

Respecting Traditional Owner cultural values

Waterways are central to the living culture of Aboriginal Victorians. Strategic planning must support Aboriginal self-determination by involving Traditional Owners from the outset of any project.

Traditional Owners have managed water and Country for millennia. Places near waterways often hold cultural significance and may contain physical evidence of past occupation. Incorporating Traditional Owners’ cultural values into planning and management of waterways and surrounding land, now and into the future, is a foundational aspect of enabling them to care for their Country and fully exercise customary, cultural, economic and spiritual rights to water.

Planning should:

- be guided by relevant Country Plans or other Traditional Owner strategies

- engage Traditional Owners as project partners where possible

- reflect their values and aspirations in long-term waterway protection.

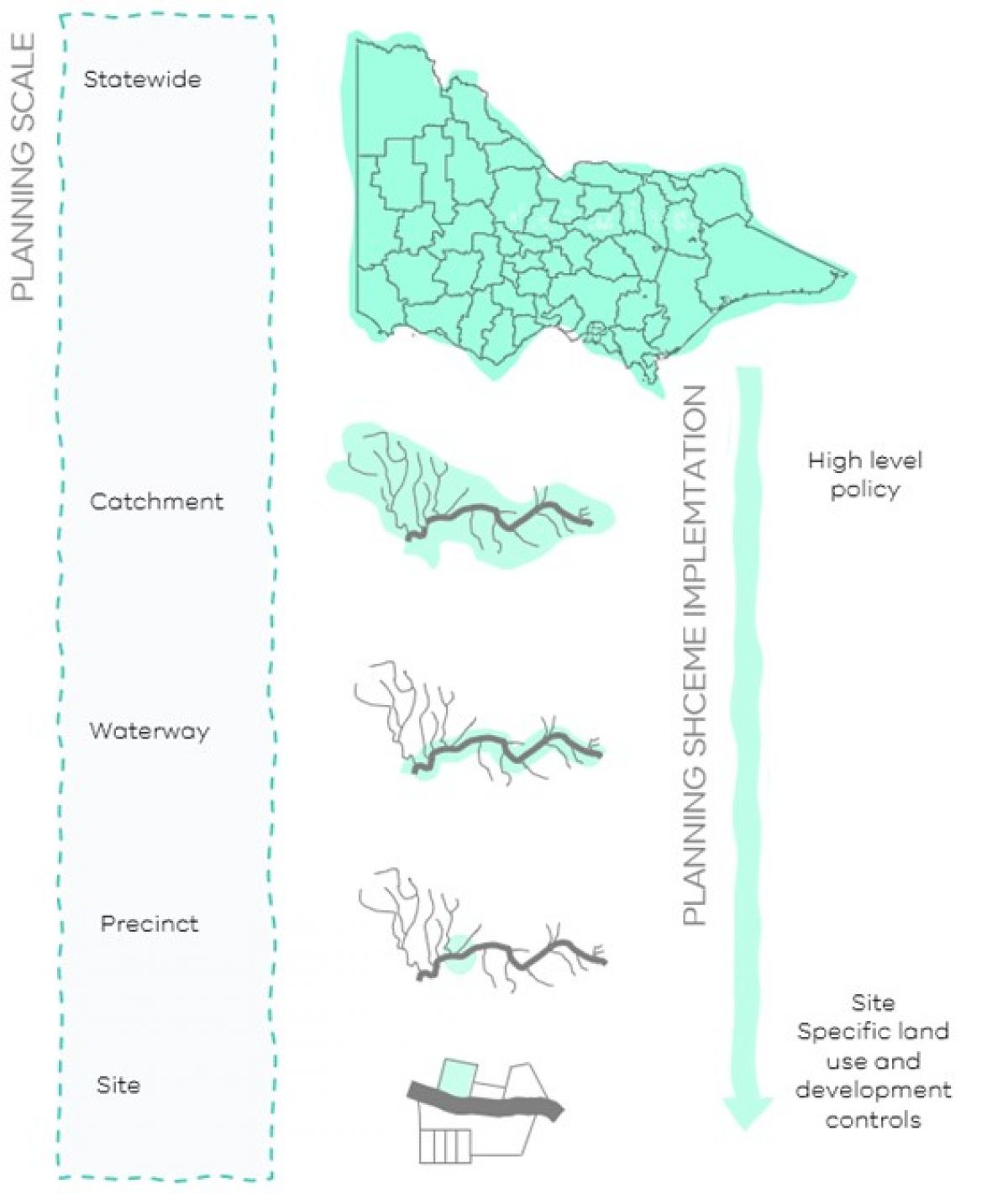

Planning for waterways at different strategic scales

Strategic planning for waterways can be undertaken at strategic scales – from state to catchment-wide frameworks through to individual waterway planning. Even on an individual site scale, strategic planning for waterways can be considered. Each scale plays a distinct role in supporting nature-based solutions that protect and enhance the health of waterways and surrounding land.

Whole-of-waterway planning is important because it enables a coordinated, systems-based approach that protects the long-term health, identity and community value of waterways. It ensures that actions taken at one location support, rather than undermine, broader ecological, cultural and planning objectives.

However, waterway planning can also be undertaken effectively for individual reaches or at a sub-catchment scale to address specific issues or opportunities. The critical consideration is to design the planning scope based on the inherent values and characteristics of the waterway itself, not just administrative boundaries or place-based precinct boundaries. Planning scales include:

- Statewide covers all waterways, rivers, creeks, lakes, wetlands and billabongs across the state. This scale recognises waterways as interconnected systems that contribute to the statewide ecological health, cultural values and resource management. The statewide scale informs strategic policy and planning across regions and catchments.

- Catchment or sub-catchment covers the entire area where rainfall and runoff naturally drain into a waterway. This scale of waterway planning is useful in managing runoff, coordinating land uses, determining the cumulative impacts of land use and development upon the waterway and alignment across administrative boundaries.

- Waterway corridor focuses on the land and environment directly surrounding a waterway. This scale can be used in protection of riparian zones, floodplains or habitat, managing urban interfaces with the waterway or identifying and protecting cultural values.

- Reach or precinct targets smaller sections of a waterway corridor requiring focused intervention or enhancement. This scale is useful for restoring habitat, upgrading infrastructure, place-based urban development and cultural values protection.

- Site focuses on an individual location within the waterway corridor. This scale considers its immediate interfaces and surrounding context. This scale is useful for assessing direct or localised impacts, such amenity, access, biodiversity and cultural values at a specific point along a waterway.

Planning at multiple scales allows interventions to be integrated and sequenced. Broader-scale planning helps identify:

- natural assets to retain and enhance

- opportunities to connect and restore waterway corridors

- locations where nature-based solutions can deliver multiple benefits, including biodiversity, cooling, flood mitigation and access

- ecological buffers, land use transitions and floodplain protection.

Precinct or neighbourhood-scale planning can then apply this direction to guide land use change, inform rezoning and shape development and infrastructure.

Using a multi-scalar approach also supports integration between land use and water planning, and ensures decisions reflect the values of Traditional Owners, agencies and the community.

State and regional strategies, such as Victorian Waterway Management Strategy, Healthy Waterways Strategy, and regional catchment strategies, reflect this approach and provide a shared evidence base for planning.

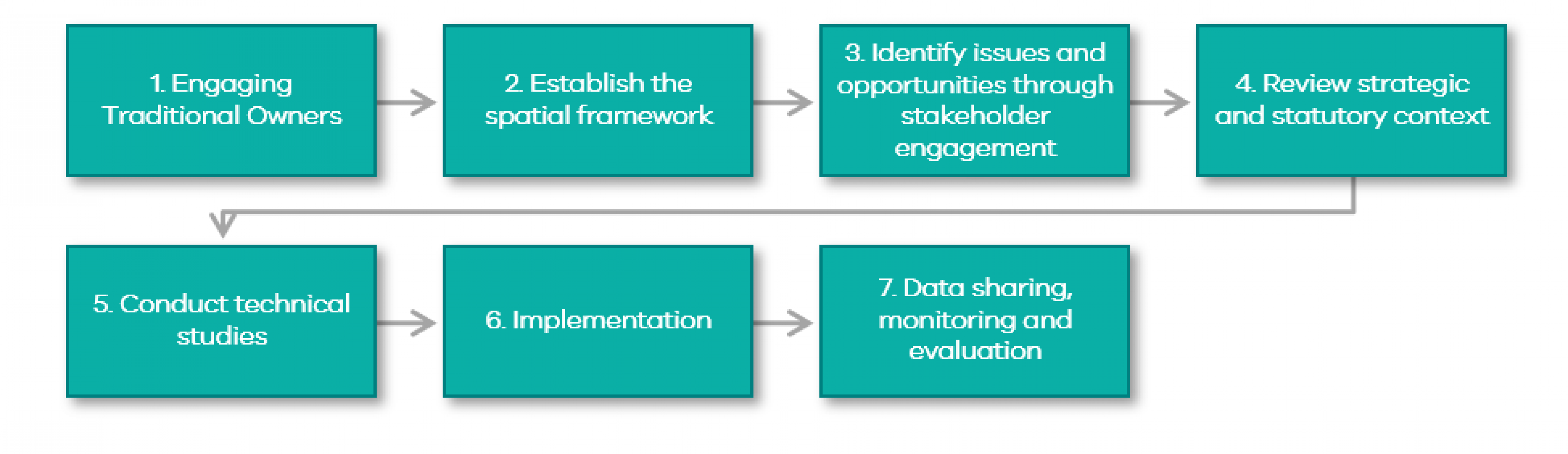

A strategic approach to planning for waterways

Strategic waterway planning involves a range of steps that help guide the development of policies, planning controls and local strategies. Through strategic planning and following the steps in the figure below, a considered approach to evaluating how a proposal, amendment or policy will enhance and protect waterways, can be achieved.

While not all projects will require every step to be undertaken, considering them early and throughout the planning process supports more integrated, effective outcomes.

1. Engaging Traditional Owners

Engaging with Traditional Owner groups at the earliest stages of a project ensures their knowledge and aspirations shape the scope and direction of planning work.

Relevant Registered Aboriginal Party (RAP) Country Plans or other strategic documents should inform planning approaches. Country Plans articulate long-term visions, goals, principles for engagement and measures of success in caring for Country and provide essential context for respectful and effective collaboration.

2. Establishing the spatial framework

A clear spatial framework is essential for effective waterway planning. This begins with defining the waterway corridor, the area directly connected to and influenced by the waterway and extends to determining the broader study area for strategic analysis.

The waterway corridor

A typical waterway corridor includes:

- The waterway itself —the river, creek or wetland including its bed and banks.

- The riparian zone — land and vegetation immediately beside the waterway.

- Floodplains — areas that flood during high water flows.

- Cultural and recreational sites — trails, parks and places of cultural significance.

Rather than relying on administrative or other planning boundaries, it is important to use natural features such as hydrology, topography and ecological connectivity to delineate the corridor. The width of the corridor will vary depending on the landscape context. For example, the corridor may be narrow where a waterway is deeply incised into steep terrain, but broader across flat, flood-prone areas.

For Traditional Owners, specific places within waterway corridors (such as confluences, wetlands, billabongs and estuaries) often hold high cultural significance. These places may require wider buffers or more protective planning controls to safeguard their values.

In defining the waterway corridor, consider:

- Clause 12.03-1S of the Victorian Planning Policy Framework: Requires a minimum 50-metre setback from the top of each bank.

- Clause 12.03-1S of the Victorian Planning Policy Framework: Applies to the area 200 metres from the waterway centreline to protect broader ecological, hydrological, cultural, and recreational values. In some instances, it may be appropriate to consider land beyond 200 metres.

- All land within 200 metres of a named waterway: Is an area of Aboriginal cultural heritage sensitivity, under the Aboriginal Heritage Regulations.

The study area

Beyond the corridor, the study area sets the broader spatial context for strategic planning. This area includes the full waterway system and associated environmental, social and cultural factors that influence waterway health and community value.

Determining the study area requires careful consideration, ideally in collaboration with Traditional Owners, to ensure inclusion of culturally significant or sensitive landscapes.

Factors that can help define the study area include:

- Topography and floodplain extent

- Biodiversity, habitat and vegetation zones

- Nearby open spaces and parklands

- Social and recreational uses and infrastructure

- Urban and riparian interface areas

- Locations of cultural heritage sites

- Key views to and from the waterway

- Potential downstream or upstream impacts

- Areas of known Traditional Owner values.

For complex waterways, the study area may extend further to provide a comprehensive understanding of the system’s interactions and values.

3. Identifying issues and opportunities through stakeholder and community engagement

Waterway planning benefits from early and ongoing engagement with a wide range of stakeholders and communities. Understanding existing challenges or future opportunities helps create shared visions and coordinated approaches. Because waterways often cross multiple jurisdictions, collaboration across agencies and groups is essential.

Table 1: Waterways planning key partners and stakeholders

| Stakeholder | Role / Responsibility |

|---|---|

| Traditional Owners | Must be consulted by the planning authority at the project outset to determine their preferred level of involvement in the project. |

| Catchment Management Authorities (CMAs) | Must be consulted on planning and development matters including in the assessment of permits and in the development of strategies and water management studies. Melbourne Water manages Melbourne’s catchment. |

| State government departments | Oversee and implement Victoria’s planning system and framework and manage Victoria’s water resources through policy, legislation and programs. Should be consulted on significant planning or policy changes involving waterways or nearby areas. |

| Municipal councils | May initiate planning scheme amendments as the planning authority and are responsible for most planning permit decisions, unless the Minister for Planning is involved. |

| Public land managers | Should be consulted at the project outset. They include Parks Victoria, Melbourne Water and CMAs. |

| Committees of management | Should be consulted at the project outset, as relevant. Some waterways have committees of management to manage Crown land reserves within the waterway corridor. |

| Community groups | Active in the care and management of waterways, with local knowledge and ideas (e.g., ‘Friends of’ groups, associations, riverkeepers). Consult earlier in project development and as needed. |

| Landowners and the community | Should be consulted at project milestones or as needed. |

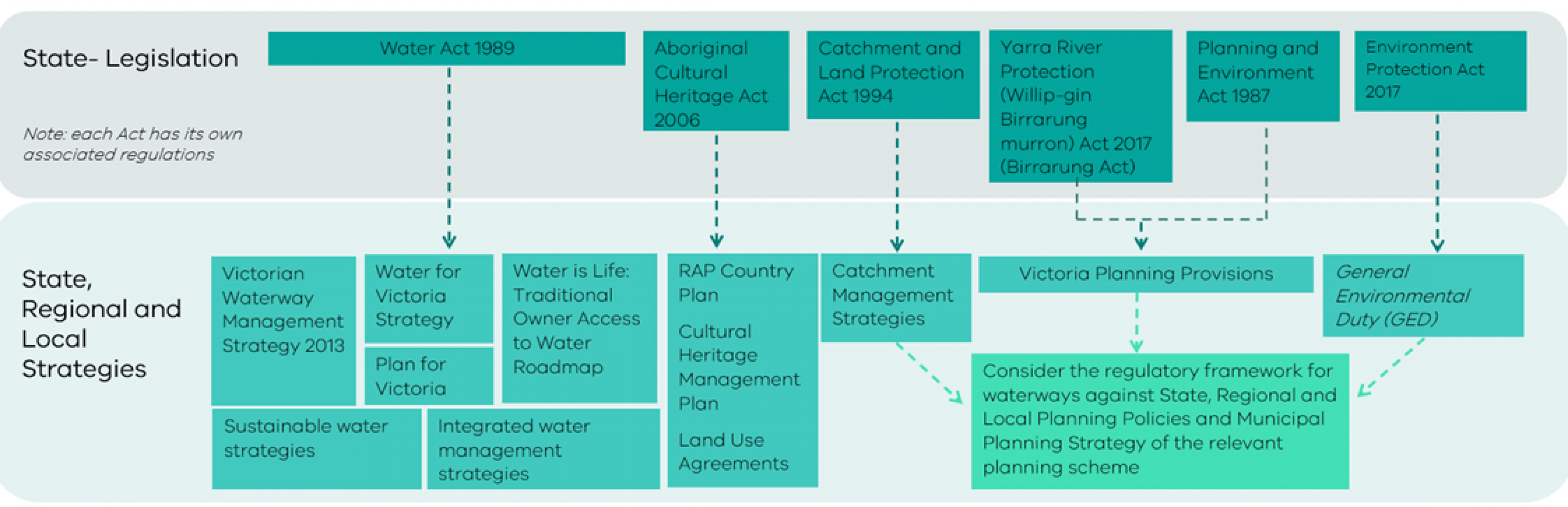

4. Reviewing the strategic and statutory context for waterway planning

A thorough review of the existing legislative, policy and planning framework ensures that waterway planning aligns with current requirements and identifies any gaps.

This includes state and local planning policies, relevant legislation, regulations and regional or catchment strategies. Understanding these layers enables planners to work effectively within the statutory environment and informs the scope and nature of necessary planning controls.

5. Conducting technical studies

Technical studies provide evidence and analysis to support strategic planning and decision-making. Depending on the context, these might include flood studies, landscape assessments, biodiversity surveys, access and movement analyses, or master planning for specific sites.

These studies help define key waterway features, assess risks and opportunities, and recommend appropriate management or protection measures. Outputs often inform the application of planning controls such as overlays or precinct plans.

Table 2: Examples of technical studies for waterways planning

| Type of study | When to use / benefits provided | Key outputs |

|---|---|---|

| Landscape assessment | Broad application along a full waterway or a waterway reach Identifying the waterway corridor holistically, as a living entity Acknowledging Traditional Owner values Alignment across administrative areas | Significant Landscape Overlay (SLO) |

| Biodiversity study | Support protection of biodiversity values Applied at a broad scale or to a localised place | Environmental Significance Overlay (ESO) Clause 52.16 Native Vegetation Precinct Plan |

| Urban design and visual impact assessment | Applied to a local area or site Achieving a desired visual outcome for a waterway environment Protect key views from waterway corridors | Design Development Overlay (DDO) |

| Cultural heritage management plan | Details specific actions for management and protection of a significant place | Incorporated document |

6. Implementation

Combining insights from community and stakeholder engagement with technical studies helps identify the key challenges, opportunities and practical strategies. These strategies may then inform a formal plan or directly guide updates to planning schemes.

Implementation priorities will vary depending on the values of the waterway and the outcomes sought. They may include policy updates, infrastructure upgrades, revegetation or new planning controls. Coordinating these actions across agencies and levels of government is essential to success.

In some cases, strategic planning leads to an integrated strategy or adopted plan. In others, the findings from technical work may be sufficient to directly support changes to a planning scheme or guide decision-making.

Implementation options

Planning authorities can draw on a wide range of strategic directions, policies and planning controls to strengthen the protection and enhancement of waterways. Where gaps in statutory protection are identified, a planning scheme amendment may be required to update or introduce relevant policies and controls.

Planning scheme amendments may be initiated by municipal councils or the Minister for Planning and should reflect the nature and context of the waterway, as well as the outcomes of any relevant strategic work, such as a waterway strategy or background study. Table 3 provides examples of implementation tools and how they can be used in different contexts.

Table 3: Waterways planning implementation options

| Implementation option | What it does | When to use |

|---|---|---|

| PPF local policies | Sets waterway objectives in decision making at the local level | To address specific local requirements |

| Overlays | Can require a permit for buildings, works or subdivision | To protect a specific waterway value, or integrated set of waterway values Can be applied across public and private land and municipal boundaries |

| Zones | Regulates land uses adjacent to a waterway | When changing primary land use to secure long term environmental outcomes such as protected habitat |

Strategic justification

Most implementation options will require a planning scheme amendment. Strong strategic justification is necessary to support any amendment. This includes:

- Early engagement with the relevant Traditional Owner group or RAP to enable them to determine the issues of importance and their preferred level of involvement.

- Early engagement with the relevant water authority and/or CMA.

- Clear links to the relevant catchment management plan and/or waterway strategy.

- Engagement with referral authorities, such as the Country Fire Authority.

- Consideration of the interface between waterways and adjacent urban or rural areas.

- Engagement with affected landowners and local communities.

- Alignment with state government policies.

7. Data sharing, monitoring evaluation and learning

Indigenous Data Sovereignty

Indigenous Data Sovereignty is the right of First Peoples to own and control their data, knowledge and information that is about them or relates to them, and to govern how and what information is collected, owned and used. How data is to be collected and used must be agreed at the project commencement.

Monitoring and evaluation

Monitoring and evaluation are essential to understanding how planning outcomes impact waterway health and community values over time. Including these considerations early ensures that strategic planning is adaptive and can evolve based on evidence.

Key terms and concepts

The following terms and concepts are commonly used from a planning perspective in legislation, planning provisions and strategies.

Areas of Aboriginal cultural heritage sensitivity: The Aboriginal Heritage Regulations give effect to the Aboriginal Heritage Act 2006. They define what are referred to as ‘areas of cultural heritage sensitivity’, which are places where Aboriginal cultural heritage is considered more likely to arise. This includes all land within 200 metres of named waterways and coastal land, all parks as defined under the National Parks Act 1975 (Vic), Ramsar wetlands and a range of specified landforms such as high plains, stony rises, dunes and caves.

Blue-green infrastructure: Involves deploying infrastructure through an integrated water management approach with recycled water systems, stormwater harvesting schemes for urban irrigation, vegetation features and constructed wetlands to treat stormwater runoff for improved environmental conditions and community benefits.

Catchment: An area where water falling as rain is collected by the landscape, eventually flowing to a body of water such as a creek, river, dam, lake, ocean or into a groundwater system.

Catchment management authorities: The Catchment and Land Protection Act 1994 established 10 catchment and land protection regions, each with a catchment management authority (CMA) responsible for the integrated planning and coordination of land, water and biodiversity management. CMAs have specific powers under Part 10 of the Water Act 1989.

Centreline: The midpoint along the length of the stream or river where the edges have been previously delineated. The centreline is commonly used to determine the 200-metre area of Aboriginal cultural heritage sensitivity, under the Aboriginal Heritage Regulations 2018.

Estuary: Where a river meets the sea, including the lower section of a river that experiences tidal flows where freshwater and saltwater mix. Usually, an estuary must be at least 1 kilometre in length or have a lagoon greater than 300 metres in length. The downstream extent of an estuary is where the banks of the river end and the waterway meets the bay or ocean.

Groundwater: All subsurface water, generally occupying the pores and crevices of rock and soil.

Instream: The component of a river within the river channel, including pools, riffles, woody debris, the riverbank and benches along the bank.

Integrated catchment management: The coordinated management of land, water and biodiversity resources based on catchment areas. It incorporates environmental, social, cultural and economic considerations. This approach seeks to ensure the long-term viability of natural resource systems and human needs across current and future generations.

Integrated water management (IWM): A collaborative approach to planning that brings together all elements of the water cycle including sewage management, water supply, stormwater management and water treatment, considering environmental, economic and social benefits.

Reach: Smaller sections of a waterway corridor where characteristics are similar.

Riparian land: Land a minimum of 50 metres either side of a waterway measured from the top of the bank with or without areas of vegetation.

River basin: The land into which a river and its tributaries drain.

River basin verses catchment: There are 46 river basins within Victoria which make up 10 catchment regions managed by the relevant Catchment Management Authority (CMA).

Rivers: Rivers, creeks and smaller tributaries, including the water, bed, banks and adjacent land (known as riparian land).

Sodic soil: Soil with a high proportion of sodium. This excess sodium disrupts the soil's structure, leading to problems like poor water infiltration, reduced plant growth and increased erosion risk.

Waterway corridor: The full extent of the waterway, from the headwaters to the sea with a minimum corridor width of 50 metres either side of the waterway measured from the top of the bank. The width of the corridor may extend up to or beyond 200 metres from the centreline of the waterway to define a broader waterway policy area, which will also include potential areas of Aboriginal cultural heritage sensitivity. The Birrarung corridor is defined differently to other waterway corridors in Victoria and includes all land (other than excluded land under the Birrarung Act) located within 1 kilometre of a bank of Birrarung.

Top of bank: The point along the bank of a stream where an abrupt change in slope is evident, and where the stream is generally able to overflow the banks and enter the adjacent floodplain during a flood event. Unless otherwise stated, setbacks and buffer areas should be measured from this point. Top of bank is the preferred point of measurement, as waterways change and move overtime. The top of bank is considered more reliable and any change to is likely to occur slowly over time.

Tributary: A stream or river that flows into a larger waterway.

Urban Heat Island Effect (UHIE): When the built environment absorbs, traps and in some cases directly emits heat, causing urban areas to be significantly warmer than surrounding non-urban areas.

Waterway amenity: People’s experience of the naturalness, escape and safety of waterways. Amenity includes the character of the landscape and the vistas and views from and to the rivers, the level of overshadowing from development, the cultural values associated with the waterways, as well as the parklands and open spaces along them.

Waterway condition/waterway health: Umbrella terms for the overall state of key features and processes that underpin the functioning of waterway ecosystems.

Disclaimer

This publication may be of assistance to you but the State of Victoria and its employees do not guarantee that the publication is without flaw of any kind or is wholly appropriate for your particular purposes and therefore disclaims all liability for any error, loss or other consequence which may arise from you relying on any information in this publication.

Page last updated: 23/12/25